.

Two Significant Turkish Profiles at Princeton University in the 1960s:

A Perspective on the Transformative Landscape of Cross-Cultural Exchanges between Turkey and the U.S.

'

As an architect and an economist, Bilgi Denel (1937, Istanbul- present) and Sener Ozsahin (1944, Gelibolu- present) are two graduates of Princeton University in the 1960s. In relation to the new geopolitics order in the world and cross-cultural exchanges between postwar Turkey and the US, the first-hand experience of these two significant figures has a potential to shed light on the emerging dynamics of culturally responsive teaching and learning milieu in universities in North America in that period and their influences on the constructive operations of gender within such a context. As they expressed, Bilgi Denel, one of the very few foreign students at Princeton University was the first “qualifying student with an engineering background from Turkey” at the School of Architecture in 1959. Considering cultural difference as an important resource in teaching, learning and the production of knowledge, his formative years were shaped by Professor Labatut and Professor Lickleider; and those years gave a transformative motivation for his academic career in Turkish and the US architecture. As a second significant figure, Sener Ozsahin’s decision to study at Princeton University was shaped by his close dialog with Mr. Carl Tobey, his first English teacher in Turkey and a graduate of Princeton University (Class of ’40). Pursuing his education as the first Turkish citizen to earn a Princeton undergraduate degree, he studied economics and his roots in this field come from Prof. W. Arthur Lewis, Prof. Frederic Harbison, Prof. Mancur Olson and Prof. William J. Baumol. Obtained his degree in Economics in 1966, he conducted a successful professional career at OYAK (Turkey’s first and privately-owned pension fund) and some leading holdings, such as Sabanci and Ekinciler in Turkey, and played an important role in organizing and promoting activities and dialogs among the graduates of Princeton in his native country, as the founder and the first president of the Alumni Association of Princeton University in Turkey. In the following interviews, their answers provide a significant contextual grounding for understanding the multicultural perspective evolving in North America in the 1960s and its impact on higher education as well as the gender’s multiple roles in constructing both cross-cultural exchanges and the exploration of new knowledge in their disciplines and professions. These two figures and their career paths also indicate why there is still a need more inclusive scholarly studies on history in relation to their special fields in that time period: In order to complete the record of the past and explore the historical production of gender knowledge within a multiple perspective.

.

Meral Ekincioglu, Ph.D.

Cambridge, MA, June 24th 2016.

'

As an architect and an economist, Bilgi Denel (1937, Istanbul- present) and Sener Ozsahin (1944, Gelibolu- present) are two graduates of Princeton University in the 1960s. In relation to the new geopolitics order in the world and cross-cultural exchanges between postwar Turkey and the US, the first-hand experience of these two significant figures has a potential to shed light on the emerging dynamics of culturally responsive teaching and learning milieu in universities in North America in that period and their influences on the constructive operations of gender within such a context. As they expressed, Bilgi Denel, one of the very few foreign students at Princeton University was the first “qualifying student with an engineering background from Turkey” at the School of Architecture in 1959. Considering cultural difference as an important resource in teaching, learning and the production of knowledge, his formative years were shaped by Professor Labatut and Professor Lickleider; and those years gave a transformative motivation for his academic career in Turkish and the US architecture. As a second significant figure, Sener Ozsahin’s decision to study at Princeton University was shaped by his close dialog with Mr. Carl Tobey, his first English teacher in Turkey and a graduate of Princeton University (Class of ’40). Pursuing his education as the first Turkish citizen to earn a Princeton undergraduate degree, he studied economics and his roots in this field come from Prof. W. Arthur Lewis, Prof. Frederic Harbison, Prof. Mancur Olson and Prof. William J. Baumol. Obtained his degree in Economics in 1966, he conducted a successful professional career at OYAK (Turkey’s first and privately-owned pension fund) and some leading holdings, such as Sabanci and Ekinciler in Turkey, and played an important role in organizing and promoting activities and dialogs among the graduates of Princeton in his native country, as the founder and the first president of the Alumni Association of Princeton University in Turkey. In the following interviews, their answers provide a significant contextual grounding for understanding the multicultural perspective evolving in North America in the 1960s and its impact on higher education as well as the gender’s multiple roles in constructing both cross-cultural exchanges and the exploration of new knowledge in their disciplines and professions. These two figures and their career paths also indicate why there is still a need more inclusive scholarly studies on history in relation to their special fields in that time period: In order to complete the record of the past and explore the historical production of gender knowledge within a multiple perspective.

.

Meral Ekincioglu, Ph.D.

Cambridge, MA, June 24th 2016.

.

.

Bilgi Denel: A 45 Year Teaching Career in Architecture

.

Meral Ekincioglu: Dear Bilgi Denel, you are one of the pioneering figures who opened up new horizons for his students in architecture. Could you share your background in Turkey and in the US?

.

Bilgi Denel: I was born in Istanbul, in 1937, and grew up in Ankara. After my elementary school in Ankara, my father took me to Istanbul, to take something they called “tests” for three days at Robert College. I had no idea what these were, but I thought they were entertaining; also, father had said that he would buy me a bike! I did get in (though the bike came much later!) and I was made a boarder. That meant I had to stay there even during the weekends since my family lived in Ankara then. To me, this place felt like a dungeon; I even refused to learn English – until I discovered the library, with thousands of books! This made the “dungeon” disappear for an eleven year old child! In Robert College, I continued into its higher education program, and I graduated with a Degree in Civil Engineering in 1959. Engineering was a field my father thought as a good option, as the popular tendency in those years. Over the years, I had considered other venues and decided that architecture would have been much better for my abilities.

.

ME: How did you decide to pursue your education at Princeton University?

.

BD: I chose Princeton University somewhat arbitrarily. During the summer of my junior year, I wrote to a number of Graduate Schools of Architecture. I applied to 12 of those; I was accepted by 10. The Dean of the School of Architecture at Pennsylvania University, Holmes Perkins, interviewed me in Ankara and made an excellent offer to me. At the same time, Penn wrote to me that, as a foreign student, I could get very inexpensive season tickets to the Philadelphia Philharmonic. Being a music lover, I thought that I would spend all my time at concerts, and not find time to concentrate on my studies. That made me decline Penn! I decided on Princeton as a second choice. They informed me that I would be a qualifying student to take a whole bunch of undergraduate and graduate classes during the first year; I would do the regular graduate program starting the second year.

.

Bilgi Denel: A 45 Year Teaching Career in Architecture

.

Meral Ekincioglu: Dear Bilgi Denel, you are one of the pioneering figures who opened up new horizons for his students in architecture. Could you share your background in Turkey and in the US?

.

Bilgi Denel: I was born in Istanbul, in 1937, and grew up in Ankara. After my elementary school in Ankara, my father took me to Istanbul, to take something they called “tests” for three days at Robert College. I had no idea what these were, but I thought they were entertaining; also, father had said that he would buy me a bike! I did get in (though the bike came much later!) and I was made a boarder. That meant I had to stay there even during the weekends since my family lived in Ankara then. To me, this place felt like a dungeon; I even refused to learn English – until I discovered the library, with thousands of books! This made the “dungeon” disappear for an eleven year old child! In Robert College, I continued into its higher education program, and I graduated with a Degree in Civil Engineering in 1959. Engineering was a field my father thought as a good option, as the popular tendency in those years. Over the years, I had considered other venues and decided that architecture would have been much better for my abilities.

.

ME: How did you decide to pursue your education at Princeton University?

.

BD: I chose Princeton University somewhat arbitrarily. During the summer of my junior year, I wrote to a number of Graduate Schools of Architecture. I applied to 12 of those; I was accepted by 10. The Dean of the School of Architecture at Pennsylvania University, Holmes Perkins, interviewed me in Ankara and made an excellent offer to me. At the same time, Penn wrote to me that, as a foreign student, I could get very inexpensive season tickets to the Philadelphia Philharmonic. Being a music lover, I thought that I would spend all my time at concerts, and not find time to concentrate on my studies. That made me decline Penn! I decided on Princeton as a second choice. They informed me that I would be a qualifying student to take a whole bunch of undergraduate and graduate classes during the first year; I would do the regular graduate program starting the second year.

.

ME: Which department at Princeton University? Which years?

.

BD: Architecture Department. In 1959, I was one of the very few foreign students in architecture; the first “qualifying student with an engineering background from Turkey”. They did not quite know how to shape my program. In those early years, the school was somewhat racist and elitist, with no women students allowed. Fortunately, I had a few wonderful people who tutored me and nurtured my education. With a correct educational attitude, they observed my progress closely, trusted me, and pushed me forward at each step. The grading was pass/fail; with all passes, I was able to carry 5, 6, or more courses during a semester, spread over a variety of topics; I was always trying to catch up, and afterwards, introduced to another new challenge! Faculty and friends had a true shock once to find out that I did not even have a driver’s license when I could not design a parking lot properly! One learns quickly when one really wants this. From 1959 to 1961, my professional and cultural courses were completed (and I was able attend many great concerts as well), and after my 3rd and Senior year Graduate Design, Professor Jean Labatut, head of the Graduate Design, told me that I would be ready do my Master’s Thesis Project and finish during the 2nd semester of 1962-63.

.

ME: If you conduct a thesis at Princeton University, could you define it?

.

BD: 1959-1963. Professor Labatut was the Thesis Adviser for all Master’s Projects for all the 40+ years that he was at Princeton – a true master educator! His title was Director of Graduate Studies. Students wrote a synopsis of what they will work on, in 100 words. Of course, I wanted to work on something big, tall, and heroic! He ordered me to do housing “indigenous” to Turkey! I did not quite know what that would encompass; this was the word we used before “vernacular” became fashionable.

.

When I told him that I did not know much about Turkish Indigenous Architecture, Professor Labatut intervened: They gave a scholarship money for that summer and sent a Turk (me) to Turkey, to learn something about Turkish vernacular architecture. My Master’s Thesis project was to design seven elementary village schools in the seven climactic regions of Turkey, using local materials available materials, climactic, and social factors, etc. I had 22 of 30X40” boards in color, where the reviewer could tell the different climates by my use of color on the drawings. My completed project of Master of Fine Arts in Architecture was successful and accepted. It is still at the so-called “Architecture Morgue” at Princeton, where sample graduate projects are kept as learning tools; I was told it was exhibited at the school, among a few others, as a sample of 1960s work a few years ago. This was the beginning of my life-long research on Vernacular Architecture in Turkey and elsewhere. My Ph.D. is from the Istanbul Technical University, not from Princeton.

.

ME: Is there any role model for you to conduct your career in the US, and in particular at Princeton University?

.

BD: Educators like Professor Labatut, Professor Lickleider, and others have been influential in shaping my learning and thought process. I realized early that you can not teach a student, but you can create incentives for a student to want to learn and teach himself.

.

ME: As Aliye Pekin Celik, the first woman architect from Princeton University states, you are one of the leading professors who influenced her career decision at that university. What would you like to share about your relation with her?

.

BD: In all, I had well over 6000 students. I usually have no idea in what course or time I had that person in my class since a new group comes after each semester. However, I remember Aliye very well as a bright student, also responsible with good work habits, as I think of her work in juries. I also had her husband, Metin, as my student; I remember his work being very professional for a young student. I don’t remember many details, but she asked me if I could recommend her for Graduate studies at Princeton. I was pleased to recommend her and she got in. I recommended her husband, Metin Çelik, for work at a friend’s professional office, where he worked for some 32 years or so until he retired. Both of them are very special people! I knew Aliye did very very well as a student, since a professor of mine wrote back to tell me that she became the 1st female Graduate Student of the School and graduated with honors. We were very proud of her achievements (I recently found that letter and gave it to Aliye, very proudly!). Over the years we have met socially.

.

As far as METU courses, design juries and criticisms, etc., go, Aliye would remember much better.

.

ME: Did you conduct any common project with her in the US?

.

BD: No common projects in the US.

.

ME: Do you know any Turkish women (and male) architects in the US in the same period? (In the 1960s-1970s)?

.

BD: There are a few. Some studied and returned to Turkey. METU had several programs to send their better students mostly to Penn and Pratt Institute at Brooklyn, NYC during the 1960s but I have lost contact with most by now.

.

ME: Did you return to Turkey after Princeton, or continue your career in the US?

.

BD: After Princeton starting in June, 1963, I worked for SOM in NY for over a year. The experience was fulfilling. I, then, taught at California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo, CA, Architecture Department, for a school year, to return to Turkey in 1965 for my military service duty. I applied Ministry of Education in Ankara to get my Princeton equivalence. The Ministry decided that Princeton’s degree was not so! I had to sue them, after 4 years, they concluded that I was right and I won the case and gained the right to pursue a career in architecture. In the meantime, I was offered a position to teach at METU; I accepted and stayed on.

.

In 1980, I accepted a position at Cal Poly State University, where I had taught before, in San Luis Obispo, CA. I chose to leave Turkey at that time since a bomb was thrown into my house in 1978. (As well as two other academics’ homes in the same building). Also, the generals took over again with results I did not approve of! At Cal Poly, I taught until 2004; I retired after a 45 year teaching career.

.

ME: Did you conduct any project in Turkey and the US?

.

BD: I was one of the founders of MESA, a design build firm in Ankara, in 1969. I had a hand in the design and building of +/-20,000 affordable housing in Turkey. By 1980, I severed my ties with MESA, but kept in very close relationship until January 2015 when the company was sold. At one time I had 43 former students from among METU Architecture graduates working in very responsible positions there. I did constant consulting for the firm all those years. Aside from teaching, I did no professional work in the US.

.

ME: Thank you for this interview.

. Back Next

.

BD: Architecture Department. In 1959, I was one of the very few foreign students in architecture; the first “qualifying student with an engineering background from Turkey”. They did not quite know how to shape my program. In those early years, the school was somewhat racist and elitist, with no women students allowed. Fortunately, I had a few wonderful people who tutored me and nurtured my education. With a correct educational attitude, they observed my progress closely, trusted me, and pushed me forward at each step. The grading was pass/fail; with all passes, I was able to carry 5, 6, or more courses during a semester, spread over a variety of topics; I was always trying to catch up, and afterwards, introduced to another new challenge! Faculty and friends had a true shock once to find out that I did not even have a driver’s license when I could not design a parking lot properly! One learns quickly when one really wants this. From 1959 to 1961, my professional and cultural courses were completed (and I was able attend many great concerts as well), and after my 3rd and Senior year Graduate Design, Professor Jean Labatut, head of the Graduate Design, told me that I would be ready do my Master’s Thesis Project and finish during the 2nd semester of 1962-63.

.

ME: If you conduct a thesis at Princeton University, could you define it?

.

BD: 1959-1963. Professor Labatut was the Thesis Adviser for all Master’s Projects for all the 40+ years that he was at Princeton – a true master educator! His title was Director of Graduate Studies. Students wrote a synopsis of what they will work on, in 100 words. Of course, I wanted to work on something big, tall, and heroic! He ordered me to do housing “indigenous” to Turkey! I did not quite know what that would encompass; this was the word we used before “vernacular” became fashionable.

.

When I told him that I did not know much about Turkish Indigenous Architecture, Professor Labatut intervened: They gave a scholarship money for that summer and sent a Turk (me) to Turkey, to learn something about Turkish vernacular architecture. My Master’s Thesis project was to design seven elementary village schools in the seven climactic regions of Turkey, using local materials available materials, climactic, and social factors, etc. I had 22 of 30X40” boards in color, where the reviewer could tell the different climates by my use of color on the drawings. My completed project of Master of Fine Arts in Architecture was successful and accepted. It is still at the so-called “Architecture Morgue” at Princeton, where sample graduate projects are kept as learning tools; I was told it was exhibited at the school, among a few others, as a sample of 1960s work a few years ago. This was the beginning of my life-long research on Vernacular Architecture in Turkey and elsewhere. My Ph.D. is from the Istanbul Technical University, not from Princeton.

.

ME: Is there any role model for you to conduct your career in the US, and in particular at Princeton University?

.

BD: Educators like Professor Labatut, Professor Lickleider, and others have been influential in shaping my learning and thought process. I realized early that you can not teach a student, but you can create incentives for a student to want to learn and teach himself.

.

ME: As Aliye Pekin Celik, the first woman architect from Princeton University states, you are one of the leading professors who influenced her career decision at that university. What would you like to share about your relation with her?

.

BD: In all, I had well over 6000 students. I usually have no idea in what course or time I had that person in my class since a new group comes after each semester. However, I remember Aliye very well as a bright student, also responsible with good work habits, as I think of her work in juries. I also had her husband, Metin, as my student; I remember his work being very professional for a young student. I don’t remember many details, but she asked me if I could recommend her for Graduate studies at Princeton. I was pleased to recommend her and she got in. I recommended her husband, Metin Çelik, for work at a friend’s professional office, where he worked for some 32 years or so until he retired. Both of them are very special people! I knew Aliye did very very well as a student, since a professor of mine wrote back to tell me that she became the 1st female Graduate Student of the School and graduated with honors. We were very proud of her achievements (I recently found that letter and gave it to Aliye, very proudly!). Over the years we have met socially.

.

As far as METU courses, design juries and criticisms, etc., go, Aliye would remember much better.

.

ME: Did you conduct any common project with her in the US?

.

BD: No common projects in the US.

.

ME: Do you know any Turkish women (and male) architects in the US in the same period? (In the 1960s-1970s)?

.

BD: There are a few. Some studied and returned to Turkey. METU had several programs to send their better students mostly to Penn and Pratt Institute at Brooklyn, NYC during the 1960s but I have lost contact with most by now.

.

ME: Did you return to Turkey after Princeton, or continue your career in the US?

.

BD: After Princeton starting in June, 1963, I worked for SOM in NY for over a year. The experience was fulfilling. I, then, taught at California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo, CA, Architecture Department, for a school year, to return to Turkey in 1965 for my military service duty. I applied Ministry of Education in Ankara to get my Princeton equivalence. The Ministry decided that Princeton’s degree was not so! I had to sue them, after 4 years, they concluded that I was right and I won the case and gained the right to pursue a career in architecture. In the meantime, I was offered a position to teach at METU; I accepted and stayed on.

.

In 1980, I accepted a position at Cal Poly State University, where I had taught before, in San Luis Obispo, CA. I chose to leave Turkey at that time since a bomb was thrown into my house in 1978. (As well as two other academics’ homes in the same building). Also, the generals took over again with results I did not approve of! At Cal Poly, I taught until 2004; I retired after a 45 year teaching career.

.

ME: Did you conduct any project in Turkey and the US?

.

BD: I was one of the founders of MESA, a design build firm in Ankara, in 1969. I had a hand in the design and building of +/-20,000 affordable housing in Turkey. By 1980, I severed my ties with MESA, but kept in very close relationship until January 2015 when the company was sold. At one time I had 43 former students from among METU Architecture graduates working in very responsible positions there. I did constant consulting for the firm all those years. Aside from teaching, I did no professional work in the US.

.

ME: Thank you for this interview.

. Back Next

.

.

.

Publication:

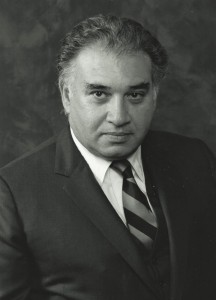

Bilgi Denel.

(Photo: Courtesy of him).